Changing the course of Water Event: from environmental racism to survival on the planet

Changing the course of Water Event: from environmental racism to survival on the planet

On the fourth floor of LIBERTÉ CONQUÉRANTE/GROWING FREEDOM: The instructions of Yoko Ono at the Fondation Phi pour l’art contemporain, the visitor, who has been so used to splashing paint on walls, hammering nails in canvas, and mending broken dishes, still has interactive Ono solo works to explore (Yes Painting is located here, along with two newer works), but this top floor is also home to a distinct exhibition within the exhibition: Water Event (1971/2019). Victoria Carrasco, Fondation Phi’s Head of Gallery Management and Event Coordination, moderated an informal panel discussion on the evening of June 6 called Water Event: An Invitation. It brought together half of the contributing artists—those in Montreal—to talk about what it was like to collaborate with Yoko Ono. As Carrasco said during her opening remarks, the exhibition is somehow both part of and apart from the rest of the works housed in The instructions of Yoko Ono at 451 Saint-Jean. Here is something a little different in kind: twelve pieces forged by a dozen Canada-based artists from Indigenous, to Quebecois-born, to immigrant and second-generation immigrant from Costa Rica, the Philippines, and Kenya. The twelve artists were hand-picked by the Fondation Phi as per Yoko Ono’s instructions, just as Lorna Bauer was for Horizontal Memories. As Carrasco pointed out after the evening’s discussion, the archive on Water Event is surprisingly thin compared to other Ono works and happenings. In this context, the Fondation Phi is happy to contribute to the archive with a video recording of the June 6 event, and a summary below of the Canadian edition.

Carrasco began the conversation with a brief account of Water Event’s inaugurating moment at the Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York, in 1971. Over the span of her career, Yoko Ono has spoken of water both as a grand equalizer and as a healing force symbolic of love. The first invitation, sent out to scores of artists, had her 1967 poem Water Talk written on the left-hand side in lowercase lettering, beneath a simple, hippie line drawing of two daisies. In the poem, human beings are bodies with essences that blur into one, containers with water inside. The metaphor of bodies as containers evokes the mystical idea of a collective soul and temporally bound, physical manifestations that seem discrete, but are in fact drops in the same ocean. “We’re all water in different containers / that’s why it’s so easy to meet,” writes Ono. Someday we’ll all evaporate together, she goes on, wryly pointing out the persistence of the ego after the water’s gone—“we’ll probably point out to the containers / and say, ‘that’s me there, that one’ / we’re container minders.” (She would go on to incorporate Water Talk in the song "We're All Water,” appearing on Some Time in New York City (1972)—available at the listening station at the Fondation Phi). Next to the daisies and poem, on the right-hand side of the invitation with the typeset arranged in the shape of a jug, is a call to produce with Yoko Ono “a water sculpture, by submitting a water container or idea of one which would form half of the sculpture. Yoko will supply the other half—water.”

For Ono’s exhibition at the Fondation Phi, the first invitation was again sent to the artists. But this time there was a supplemental invitation issued by curator Cheryl Sim on behalf of Ono. “This time Yoko wants to ask you to make or choose a ‘thing’ (a container) to put water in it [sic] for somebody specific in the world you want to give it to for an offering of water, either to change their minds, or appreciate their efforts of trying to change the world for the better or somebody or some group of people in need, desperately, for water (love).” In contrast with the first show of Water Event in 1971 (for which well over 100 artists contributed, participants were paid by Ono, and their works kept in her personal collection afterward) the current invitation outlined revised guidelines. “As this will be a collaborative work, with you sending a container or idea of a container, and Yoko Ono adding water and contributing the concept of the piece, each completed work will always have a joint authorship. After the exhibition the work will be returned to you with a documentation showing its presence in the exhibition.” Further new lines with a contemporary legalistic tone go on to stipulate: “By agreeing to this, you will be giving Yoko Ono the right to exhibit our collaborative work in the future, in the context of Water Event, and to reproduce this joint work in publications and elsewhere.”

This year’s explicit political call had a concrete effect. Some artists made their dedications front and centre, in the title or in the accompanying artist statements, some of which are as poetic as Water Talk in acknowledging the place of water in life on the planet. Of the twelve pieces on display, at least half centre on the theme of drinking water (including the last work of David Thomas, the bare-bones WATER FOR PARCHED MOUTH), especially on Indigenous reserves. Artist Shelley Niro, a member of the Six Nations Reserve, Bay of Quinte Mohawk, Turtle Clan, who was not present for the evening’s discussion, brings the only take on the crisis in water quality from an Indigenous artist within an Indigenous community. Her OUCH is a pained face crying out from underwater against the outbreak of health crises such as the scabs that have started appearing on children who swim or bathe on Indigenous reserves. Two artists who were present for the discussion, Marigold Santos and Dominique Blain, also present works that comment on the environmental racism of deteriorating water quality on Indigenous reserves, and the neglect and urgency of water treatment under the Canadian government. Geoffrey Farmer proffers a found object, a copper downpipe sourced from the detritus after Hurricane Iniki ravaged an African community he does not specify, leaving drywall, ripped-off rooftops, and deformed rain gutters in its wake. His artist statement is a poetic montage of images that ends with a cardinal pausing to drink in the calm after the storm. He and Bill Burns present depictions of species beyond the human in our ecosystem, surviving or thriving. Juan Ortiz-Apuy (whose work is detailed below) attends to the agricultural side of environmental crises. A few artists comment on the threat of big industry to the ever-increasing global population (Shelley Niro, Bill Burns, and a nod from Brendan Fernandes). Others, both present and absent for the evening’s discussion, construct homages to traditional water collection and its role in binding together communities (Filipina-born artist Lani Maestro), or sway toward highlighting the formal, aesthetic, and sensory elements of their work (Brendan Fernandes, Celia Perrin Sidarous, and Mathieu Beauséjour). Katherine Melançon keeps her scope personal and intimate in a thought piece on working through emotions.

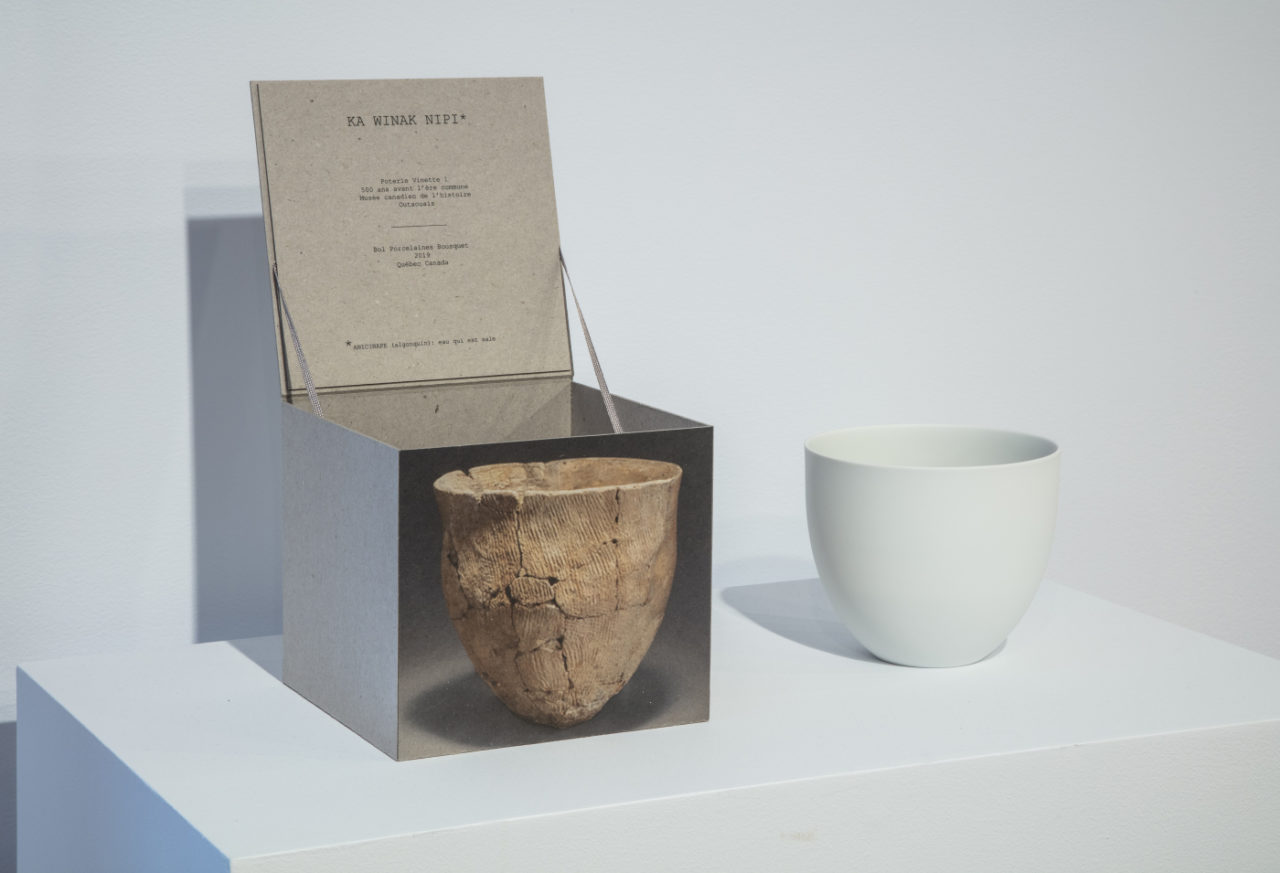

Dominique Blain spoke first, about her research-based work on First Nations water quality. Her piece is dedicated to Josephine Mandamin, the Anishinaabe grandmother who in 2003 started Mother Earth Water Walk. For years, Mandamin made an annual pilgrimage by foot, and eventually walked around all five Great Lakes carrying a container of water. Viewing Mandamin’s mission to raise awareness as an enactment of the Water Talk words, “you are water, I am water,” Blain set about creating her homage by combing the collection of the Canadian Museum of History for pottery vessels and locating one that dates back 2500 years. She determined to work with Quebecoise ceramicist Louise Bousquet, a choice she did not comment on, and on visiting her studio found a white bowl with dimensions similar to the museum artefact. Bousquet’s ceramics share the white palette of Ono’s work, but here Blain asked for a twist: for the lower fifth of the interior to be glazed black, the waterline marking the proportion of Indigenous people in Canada without access to potable water. To title the work, Blain turned again to Indigenous sources, making a cold call to an Alqonquin language school and asking for help. An Anishinaabe scholar—an elder and grandmother like Josephine Mandamin herself—agreed to a meeting in which she educated Blain about the 4000-year-old spring water in northern Quebec. Blain learned that it is a source so pure that it is tapped by the Eska bottling company, but so compromised by Australian mining operations in a neighbouring region that native access is contaminated. At Blain’s request, the elder supplied a variety of phrases for dirty tap water and dirty lake water, one of which became the title of the piece: KA WINAK NIPI. Although Blain could not remember her teacher’s name, she expressed gratitude for these crucial contributions, framing her artistic process from start to finish as a self-enriching journey.

Josephine Mandamin passed away while Dominique Blain worked on her piece, but her legacy continues, notably in the work of her water protector grand-niece, Autumn Peltier, to whom Marigold Santos has dedicated her contribution to Water Event. Santos is a Filipinx-Canadian artist who divides her time between Calgary and Montreal. Surprisingly, Santos and Blain each worked without knowledge of the other’s project. Finding similar inspiration, Blain focussed on honouring the elder Mandamin’s accomplishments, and Santos on the grave need for love, acknowledgement, and support for the young Peltier to change people’s minds. Peltier, a member of Wiikwemkoong First Nation living on Manitoulin Island in northern Ontario, found her political voice at the age of eight, speaking about the need for clean and accessible water. In 2018, at thirteen, she spoke to a United Nations general assembly about water protection. For her contribution to the exhibition, the flow of consonance, a well painstakingly constructed from layers of dripped wax, Santos aimed to combine imagery from her personal work with that of Peltier and Water Event. Her own artistic language—in sculpture, drawing, painting, and though she didn’t mention it, intricate tattoo work—is a lexicon of dripping and melting forms that are symbolic of change and transformation. As Santos noted, she used water and steam to transform solid to liquid and then waited for the liquid wax to harden again before applying the next layer. Peltier has talked of “carrying the torch” for her water walker great aunt Josephine in order to inspire change, a metaphor that reverberates with the heat Santos needed to melt the wax and engender transformation in her own work. In honouring Peltier’s commitment to her great aunt’s cause at such a young age, Santos’s piece acknowledges the difficult work ahead for future generations.

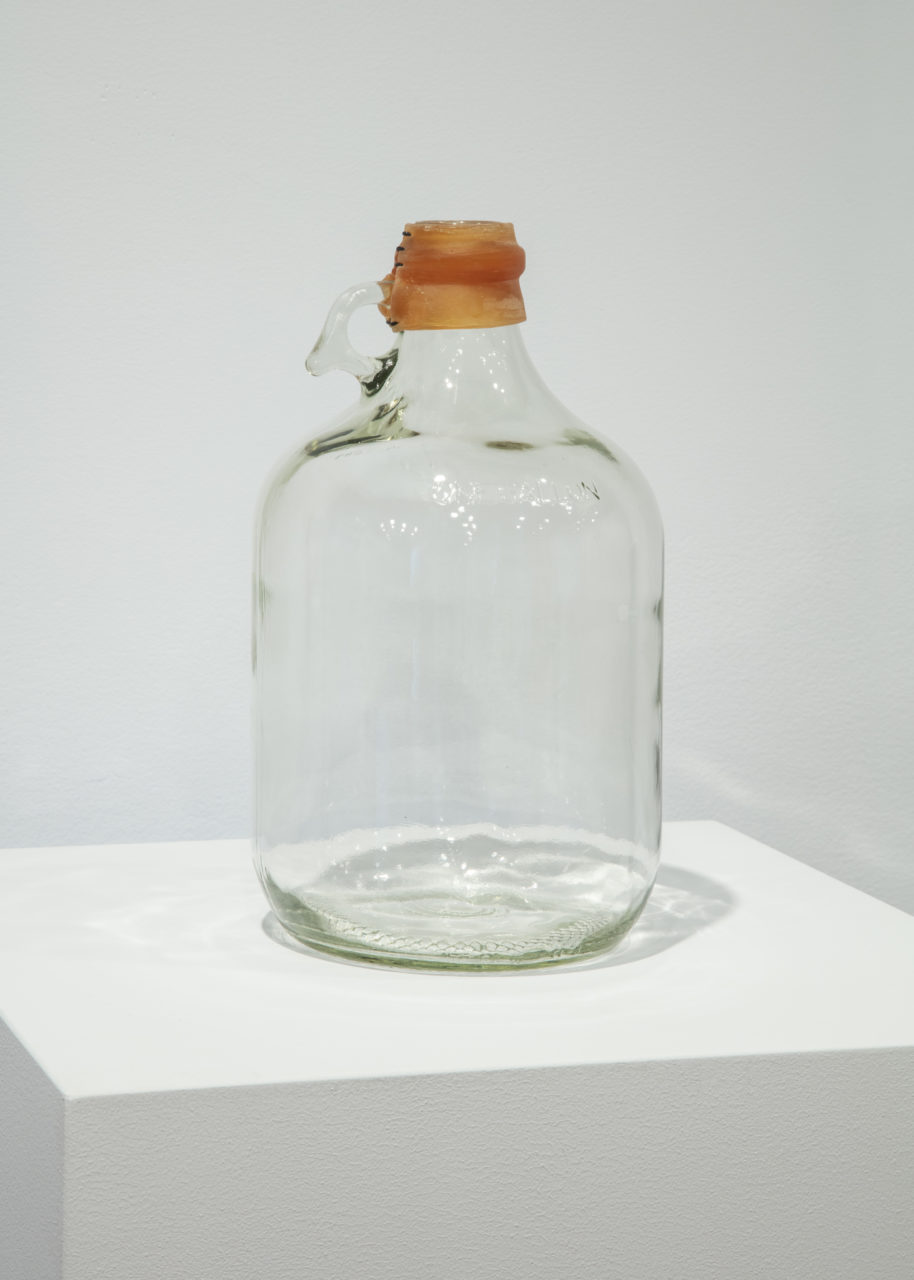

Mathieu Beauséjour spoke next, his Gallon-gut a terse and literal implementation of the instruction from Yoko Ono. Deferring to the politically informed work of the two artists who preceded him as more exciting (“palpitant”), he too focused on potable water and the fact that every person needs one gallon per day in order to survive—for drinking, eating, and hygiene. In this unit of measure, he finds a common denominator and a source of equality. He chose an industrial gallon jug lying about his workshop that might originally have been produced to sell vinegar or Coca Cola concentrate. Modelling the form on the jug’s neck on the 1971 invitation, Beauséjour moulded a piece of rubber around the mouthpiece and fastened it together at one end with large black sutures. The result, as he expressed, introduces a plasticity and carnality redolent of human lips on the jug, with all of the visceral qualities of human flesh, both sensual and repugnant. Mentioning that it should be full of water brought a giggle from moderator Carrasco, for only some of the works in Water Event have water inside them. The wording of the invitation, Carrasco explained, led most of the artists to imagine that Ono would come to make a ceremony of pouring water into all of the vessels, but in reality the choice of which vessels were deemed to receive water was another curatorial layer. This gesture resonates with the interventional layers of the institution for the larger Yoko Ono exhibition, in which Ono’s solo artworks are also assembled and mounted by the gallery according to her instructions, and not directly by the artist’s hand.

Juan Ortiz-Apuy, who came to Montreal from Costa Rica in 2003, after some deliberation settled on fashioning an object rather than using a found one. The idea of human container-minders in Ono’s Water Talk moved him, and fusing the idea of the human body as a vessel for water with a parallel notion of the body as a container for breath, Ortiz-Apuy designed a piece in blown glass. The size of the finished piece would depend on his lung capacity and technique, so he practiced by blowing up balloons with a single breath. His creation, To Future Gardens, is an outsized, ultramarine-blue watering bulb, a giant adaptation of the standard houseplant gardening accessory to fill with water and insert, stem first, into pots. In the self-watering system, dry soil releases oxygen, which in turn triggers a release of water down into the soil. Concerning himself with the precarity of future generations as Santos has done, Ortiz-Apuy envisions a landscape of motley sizes and shapes of glass globes, the roots and soil taking water to nourish themselves as needed. For Ortiz-Apuy, the very practice of filling the glass with a single human breath to reach the size he wanted evokes notions of life, death, temporality and finitude: no matter how large the bulb, the water eventually evaporates, just as the breath eventually runs out.

Picking up on this idea of evaporation, Celia Perrin Sidarous talked of a recent show she did in Oslo which informed her work here. Her tiny vessels in Oslo were filled with salt water from a Norwegian fjord and left saline rings when the water evaporated, conveying a sense of fluidity and motion between the chemical constitution of the container and its exterior. For her Blue vessel, the abstract quality of the invitation motivated her to supply something simple to the exhibition. Although Sidarous usually works in a miniaturized and meticulous table-top scale for her installations, influenced by her long-standing photography practice and the genre of still life in particular, Blue vessel is a tall, cylindrical vase shape, large enough to accommodate her forearm, as she remarked. The idea of forging and inhabiting her creation with her body ties her work to Ortiz-Apuy’s vessel, though for Sidarous, it is the trace of the hand, not the breath, that leaves what she calls a psychic charge in the made object, for her works are so minutely styled that the trace of the artist’s work is immediately evident. The description she has written for Blue vessel is both technical and poetic, a list of elements contained in the work from kaolin clay to ferrous oxide to crystalline silica, ending with the name of the glaze, moonscape, which fits the dappled, crater-like finish and its blue-grey hue. Linking her work with Ono’s through the theme of reparation, Sidarous recounted how the ceramic piece accidentally split in the first fire, and how it could have rent further during the glazed firing, but serendipitously patched itself by sealing the hole with the glaze.

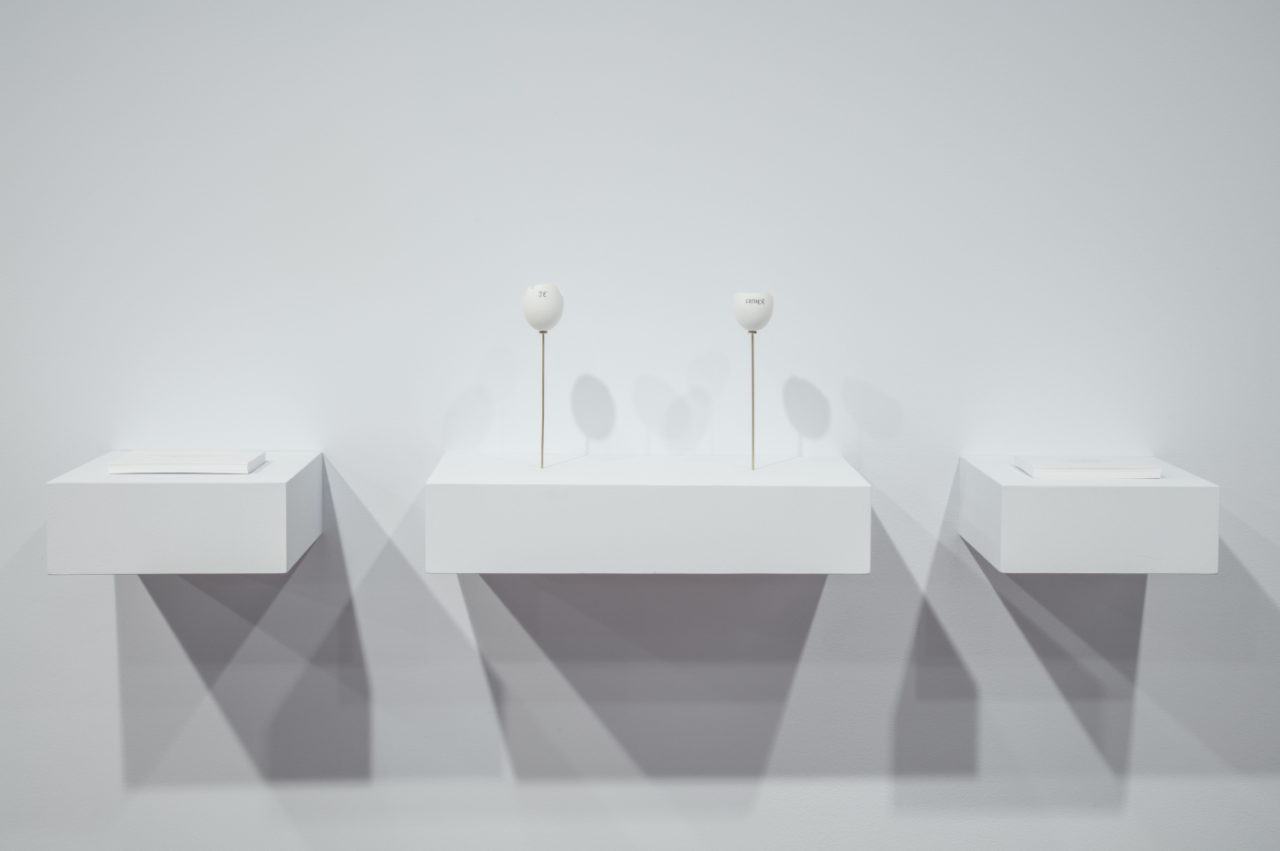

Katherine Melançon hewed the most closely to the form of Ono’s instructions, in Revolutions Start at Home II. Her goal for the work is to give a protocol for each person to create the art at home. The materials are two eggs, each to imbue and inscribe with a name: one’s own, and the name of another person “at war with themselves.” In breaking each egg, one watches past suffering pour out, and then refills the present with love. Two broken eggshells perch atop wires on a shelf, each an artefact of Melançon’s own personal and intimate engagement with the instruction. Melançon is unique among participants in departing completely from the literal task of constructing a vessel for water, and attending instead to Ono’s parenthetical suggestion that water is love. Speaking of seeing the Fondation Phi show full of instruction works for the first time in April, Melançon revealed that it occurred to her people would think her work too similar. But she views it as a response to Ono’s call in Ono’s own language, an instruction work in dialogue with all the other instruction works. Melançon invoked the potent art-historical concept of mise en abyme, the nesting of similar works one within the next, in a fractal-like sequence without end. Growing Freedom contains The instructions of Yoko Ono, which contains Water Event, which contains Revolutions Start at Home II; and each rendering of Revolutions at home has another potential personal transformation embedded within it. Nested exhibitions and instructions funnel and flow through various channels for Water Event, from the source at Yoko Ono to gallery, artist-collaborator, and intimate home practice.

After giving each speaker the floor, Carrasco proposed a few nodes for discussion. Prefacing her first question by commenting on Ono’s power to draw crowds and mobilize people to action and activism, she related that for her, it rang an ethical bell that the Fondation would not pay artists, but would ask for a contribution nonetheless. How did the artists react to the invitation on that score? Beauséjour compared the invitation to a dinner or party invitation; after accepting, one might bring a bottle of wine, and there is by no means an exchange of money. Ortiz-Apuy spoke about other aspects of the collaboration which he found challenging to adapt to. Up until Water Event, he had been used to bouncing ideas off his collaborator in a back-and-forth, but this was a more solitary process of coming to productive terms with an abstract yet specific invitation that did not immediately mesh with the concerns of his work. The struggle of the process was to find common ground, and it was important to him to find something relevant both to Ono’s practice and to his. To find the overlap, he had an opportunity to learn about Ono’s work, and this formed the bulk of his preparation and process. He landed on the intersection of activism and environmental issues, tying them to his interest in plants, gardens, and design.

In answering whether this experience of collaboration brought something to their own practice, and whether Ono’s ethos of compassion, connection, and consciousness relates to their own work, Blain stated that she wants to continue her dialogue with people she met, and lauded Ono for launching Artists Against Fracking in 2012 with her son Sean. Ortiz-Apuy noted that his piece exists not just in collaboration with Yoko Ono, but with all of the artists in Water Event. For Melançon, the exhibition was very timely after unpacking discourse around spirituality in a recent residency in Gatineau, and Beauséjour latched onto Ono’s universalist message as the salient aspect of the project. Marigold Santos revealed that she’s been a huge enthusiast of Ono’s art since she was a teenager and throughout art school. For her, the idea that a work is not complete until the viewer/participant comes to it has great appeal. Stating that her own artistic values entail an awareness of selfhood, personal vulnerability, and the need to be in touch with empathy, she went on to comment on her commonality with Ono. The considered perspective of a longtime fan rang true when she said that Yoko Ono’s practice is anchored in the individual, and in the idea of acknowledging personal vulnerability and empathy as sources of strength for human experience.

The inspiration Santos has found in teen water warrior Autumn Peltier seems based along just these lines. On Friday, September 27, 2019, while Greta Thunberg led the Montreal march against the worldwide climate crisis, Autumn Peltier was preparing to address an international audience at United Nations headquarters in New York the next day. Discussions on social media in the wake of record-breaking numbers for the demonstration centred on structural racism, and on the visibility of a figurehead like Greta versus that of an Indigenous leader like Autumn, but Peltier’s speech focused on empathy and vulnerability. “All across these lands, we know somewhere where someone can’t drink the water. Why so many, and why have they gone without for so long?”

About the Author

Shirin Radjavi is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University. She studies the art and anthropology of the Iranian online fashion imaginary, with its references to global pop culture and centuries of Iranian political and material history. She also collaborates with Iranian filmmakers on English translations of their works.

Indigenous water safety in the news

Meet Autumn Peltier, teen water warrior.

Indigenous teen Autumn Peltier addresses UN: “We can’t eat money, or drink oil.”

Wishing for a summer with clean water in Attawapiskat.

Plan to ban single-use plastics has First Nations with long-term drinking water advisories worried.

Why so few people on Six Nations reserve have clean running water, unlike their neighbours.

Ellen Page documentary on environmental racism in Nova Scotia to screen at TIFF.

Photos: Richard-Max Tremblay