On Instructions, Invitations, and Saying Yes to Imagination

On Instructions, Invitations, and Saying Yes to Imagination

By Shirin Radjavi

This article was written as part of Platform. Platform is an initiative created and driven jointly by the PHI Foundation’s education, curatorial and Visitor Experience teams. Through varied research, creation and mediation activities in which they are invited to explore their own voices and interests, Platform fosters exchanges while acknowledging the Visitor Experience team members’ expertises.

PART ONE: INSTRUCTIONS, AND THE VISITOR EXPERIENCE

Yoko Ono’s “instruction” works are central to her art. Visitors are asked to imagine, participate, and act, in works ranging from the koan-like:

Watch the sun until it becomes square. (Sun Piece, 1962 winter)

—to the refreshingly conceptual:

Each planet has its own orbit agenda.

Think of people close to you as planets.

Sometimes it’s nice to just watch them

orbit and shine. (End Piece, 1996)

—to the concretely embodied:

For playing as long as you can remember where all your pieces are. (Play it by Trust, 1966/2019)

All of these works formed part of the PHI Foundation’s exhibition this past summer, Yoko Ono: LIBERTÉ CONQUÉRANTE/GROWING FREEDOM, the first part of which was entitled The instructions of Yoko Ono. Covering text-based works gathered in the famous volume Grapefruit (1964), as well as more recent pieces that include physical props and sonic elements, these four floors emphasized the role of the visitor in the trajectory of each artwork. In different measures playful and socially engaged, it’s not a stretch to say that the most overtly political work, which was located on the third floor of 451 Saint-Jean, is so challenging and personal that it calls for existential decisions on the part of the individual. In a small, darkened screening room at one side of the floor, Cut Piece (1964) played on a loop. It is a videotaped performance in which Ono sits on stage in her best clothes with a pair of scissors next to her, and invites each member of the audience to come up one by one, and cut off a piece of her clothing.

Cut Piece was performed several times by Ono between 1964 and 1966 in Kyoto, Tokyo, New York, and London, and again in Paris in 2003. Each setting and performance has had a different flavour. In Kyoto, accounts tell of a sedate yet theatrical procession in which one man raised the scissors as if to stab Ono, then lowered them and made a simple cut. In London, press coverage led to a frenzied, even violent rush in which everyone wanted a piece of her—so to speak—predating the Beatlemania and paparazzi that would soon follow her around the globe. Most recently, in 2003, a reverential tone set in, with participants bowing before Ono and kissing her hand. In this particular recording at Carnegie Hall in 1964, Ono sits in a traditionally feminine Japanese posture, with her legs tucked beneath her and to the side, as well-dressed New Yorkers approach the stage. Finally, after a young man yanks away the front of her slip, and slices through her bra straps with a flourish, she presses her bra to her torso, her face impassive as ever. The recording ends.

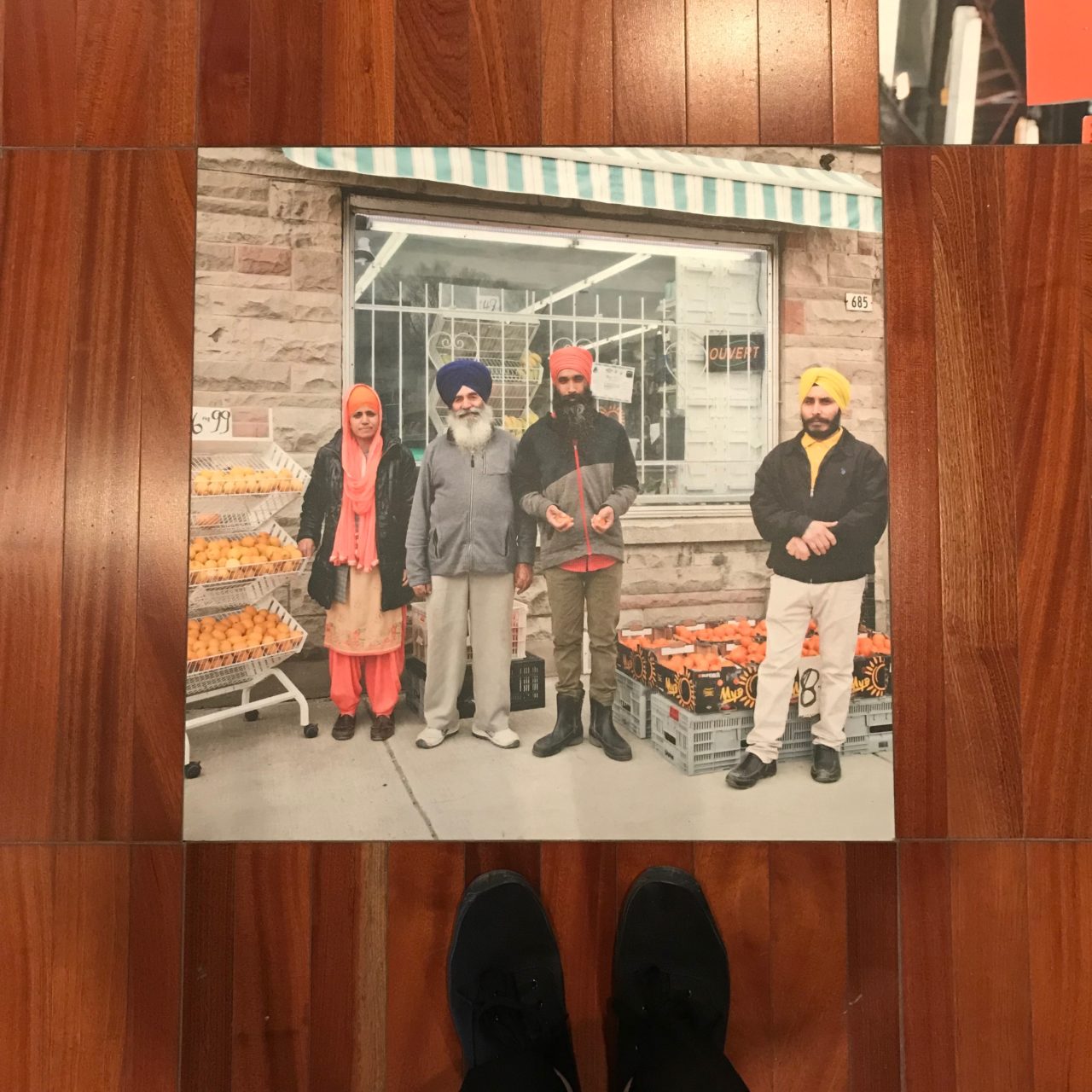

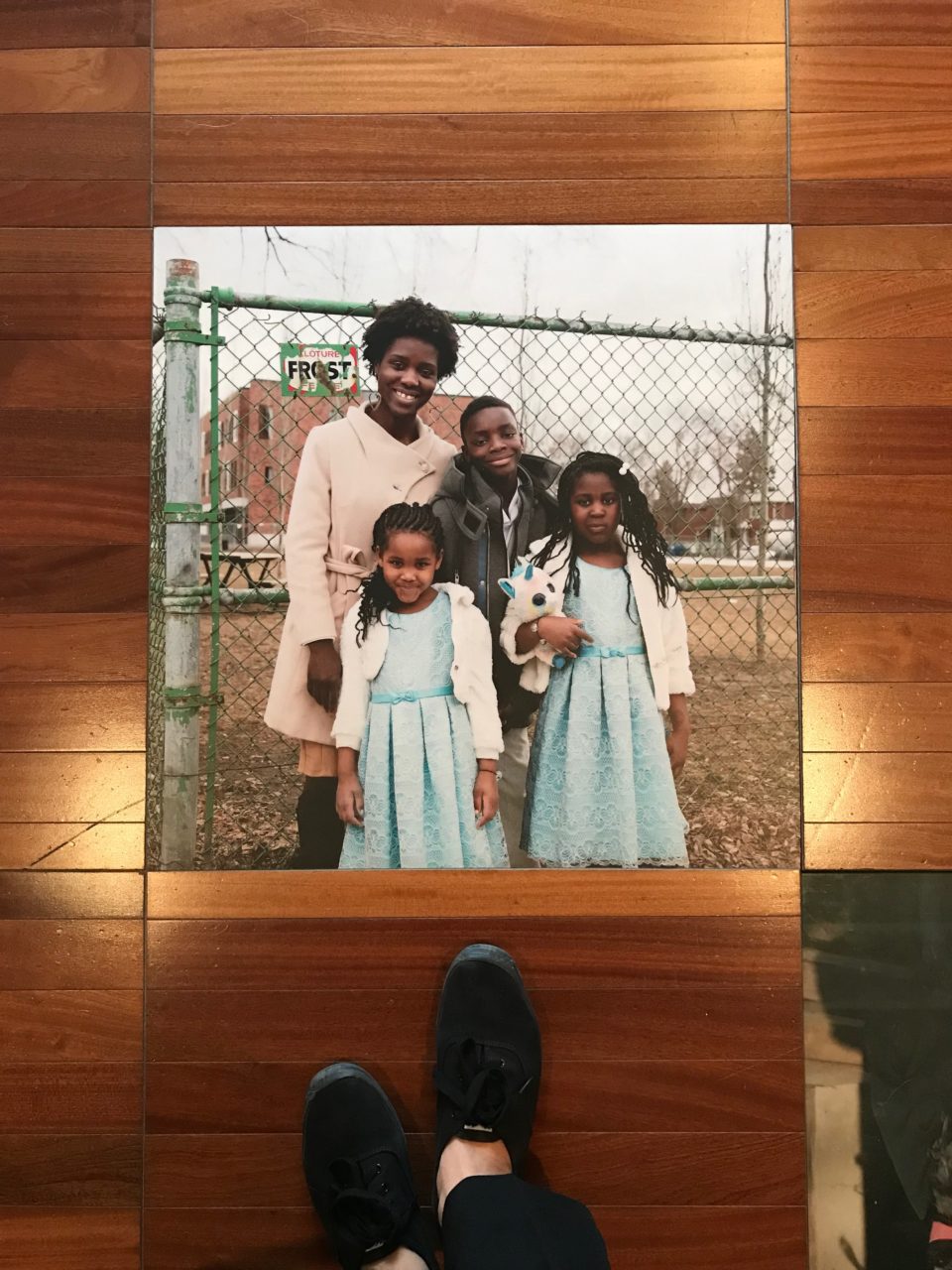

One day this past spring, a woman emerged from behind the black velvet curtain of the screening room. I learned that Amanda was backpacking from Australia. She was visibly moved by the video piece. As we spoke, she noticed the large tiles of photographs underfoot. The photos belong to Horizontal Memories (1997/2019), for which the PHI Foundation selected Montreal photographer Lorna Bauer to take pictures of “ordinary” locals in the city. Unobtrusively off to the side, a short poetic text invoked dreams, memories, lineage, legacy, and an image of shattering glass.

Amanda had not yet read it, but like many visitors, she took instinctive pains not to step on bodies and faces. And, she told me, reading the wall text confirmed her intuition not to “shatter the dreams” of immigrants and other residents of Mile End and Park Extension. Together, we came to see these pieces not just as instructions, but as invitations—invitations to do something, yes; but also, as invitations to reflect on one’s sense of entitlement.

PART TWO: INSTRUCTIONS, AND THE MODE OF RECEPTION

Ono herself has gestured toward viewing Cut Piece through different lenses at different times, and reactions to it have evolved, though not always in tandem with her statements. The earliest Japanese- and English-language reviews of the performance sensationalized it as a striptease, focusing on either gendered violence or titillation. Ono’s “event score” (i.e., instruction), published in 1966, uses a male pronoun for the performer, and a 1971 reprint of Grapefruit specifies that the performer does not have to be a woman—indeed, it was performed in 1966 and 1968 by men. However, Ono also acknowledged early on that her female body, post-pregnancy, deviated from societal beauty norms for women, and would be denigrated as such. In 1974, she spoke and wrote of a Buddhist-related notion of total, selfless artistic giving, a giving up of the ego in which people take whatever they want. At least one scholar, in 2011, stressed the parallel between her steady gaze in a seated posture, and the art of meditation. In 2003, at a press conference after her reprise in Paris at age 70, Ono told Reuters News that the piece was meant to promote world peace, performed with love against ageism, racism, sexism, and violence. This has been viewed as revisionism, but on the contrary, highlighting specific readings of her work at various times does not mean she is walking back earlier interpretations, foreclosing on others, or accommodating the art criticism vogue of the time. She has consistently espoused opening the mind up against all prejudice. The lyrics she penned with her husband to “Give Peace A Chance” in 1969 serve as a sort of reductio ad absurdum against any “-ism” one could dream up.

The last decades have sombered a one-note, feminist reception of Cut Piece into canon in the art criticism world, and reactions I encountered on the gallery floor tended to travel the same path, almost without fail. But Ono has spoken in interviews about the limited representations of Asian women in the West, which oscillate between the extremes of dragon lady and obedient slave. More to the point, she lived in Japan during World War II, where the only two atomic bombs ever deployed in war were dropped by the United States. It was an ethically questionable act, about which American President Truman said, two days after Nagasaki, “When you have to deal with a beast, you have to treat him like a beast.” Ono was a schoolchild at the time, sheltered in a family bunker in Tokyo during the firebombing of that city. After the war, her privileged family was briefly reduced to scrounging for food, and Ono called these preteen years the awakening of her aggressive side, and of her consciousness of outsider status. Though she resumed her schooling in 1946 at an elite institution where the emperor’s son was also enrolled, the scenes of destitution and humiliation on the street during the American occupation not only implanted in Japanese society a pacifist impulse that continues to this day, but was by Ono’s admission a driving factor in devoting her life to world peace. In America, both her early childhood in San Francisco and father’s continued business ties there, as well as her time living in New York just before the war and again from 1951 on, would have sensitized and exposed her personally to the racist treatment of Japanese-Americans in the United States. With all of these formative experiences, sitting quietly at Carnegie Hall for Cut Piece in 1964—the auditorium full of well-heeled, almost exclusively white American participants cutting off her clothes—she must have been aware not just of gendered dynamics, but of the colonial power, race dynamics, and intersectional issues to do with race, class, and gender that my own viewing can never escape.

There is no quote or interview excerpt in which Ono endorses a singular reading. On the contrary, her brief, elliptical instructions, and fluid, elusive commentary over time have opened up and continue to open up several possibilities. Ideas are at the core of her work, not words, but words highlight the multiple paths her artistic instigation can take. The minimal, mostly white palette of her art serves as a literal carte blanche to visitors, critics, and even to herself, to imagine, shape, and complete the work in each individual moment.

Her instructions invite reflection on one’s whim, one’s fancy, one’s creative impulse, one’s mantle of privilege, and one’s preconceptions. Cut Piece and Horizontal Memories force the participant to decide the status of an instruction for oneself, though not without input. Instructions are imperative: they tell you to do something. But just below the grammatical surface, they inspire and challenge you to consider whether you will do something, and if so, to imagine how. The conversation with Amanda, among other interactions, led me to appreciate Ono’s principle of collaboration not just in what the gallery visitor brings to the work, but also in interactions between visitor and gallery attendant. Cut Piece has seen Ono collaborate with a live audience in a cumulative, cooperative act; with individual viewers in a screening room, years later; and with gallery workers on the floor. For Horizontal Memories, Ono advised the PHI Foundation in choosing a local artist to work with. Horizontal Memories also depends on collaboration with local residents, whose consent in releasing their image was a crucial aspect of participation; and with visitors moving through the space of the gallery, choosing each step.

PART THREE: INSTRUCTIONS, AND THE GALLERY STAGING

So visitors are not the only recipients of Yoko Ono’s instructions. She issues them to artist collaborators, and to galleries that stage her work. The PHI Foundation selected Montreal artist Lorna Bauer and various Montreal neighbourhoods for Horizontal Memories. This delegation furthers Ono’s reach when she isn’t physically present. It also entrusts stewardship of her vision to locals, who can use their involvement in neighbourhood dynamics, and their familiarity with the terrain, to activate the instructions on the ground. Horizontal Memories is by no means the only piece for which Yoko Ono grants the gallery freedom to choose certain parametres.

For Helmets—Pieces of Sky (2001/2019), previous exhibits used vintage soldier helmets from long ago wars. PHI Foundation curator Cheryl Sim chose local riot police helmets to hang upside down and fill with jigsaw puzzle pieces of blue skies and white clouds. For those who demonstrated, seeing the riot helmets was surely a reminder of the use of tear gas and rubber bullets against unarmed participants in the Quebec City protests in 2001, the arrest of scores of protesters in the peaceful “green zone” against World Trade Organization meetings in 2003, or the shielded officers banging batons in unison who show up at annual Montreal marches against police brutality. Such recollections can only make the instruction “Take a piece of sky. Know that we are all part of each other,” that much more poignant and fraught.

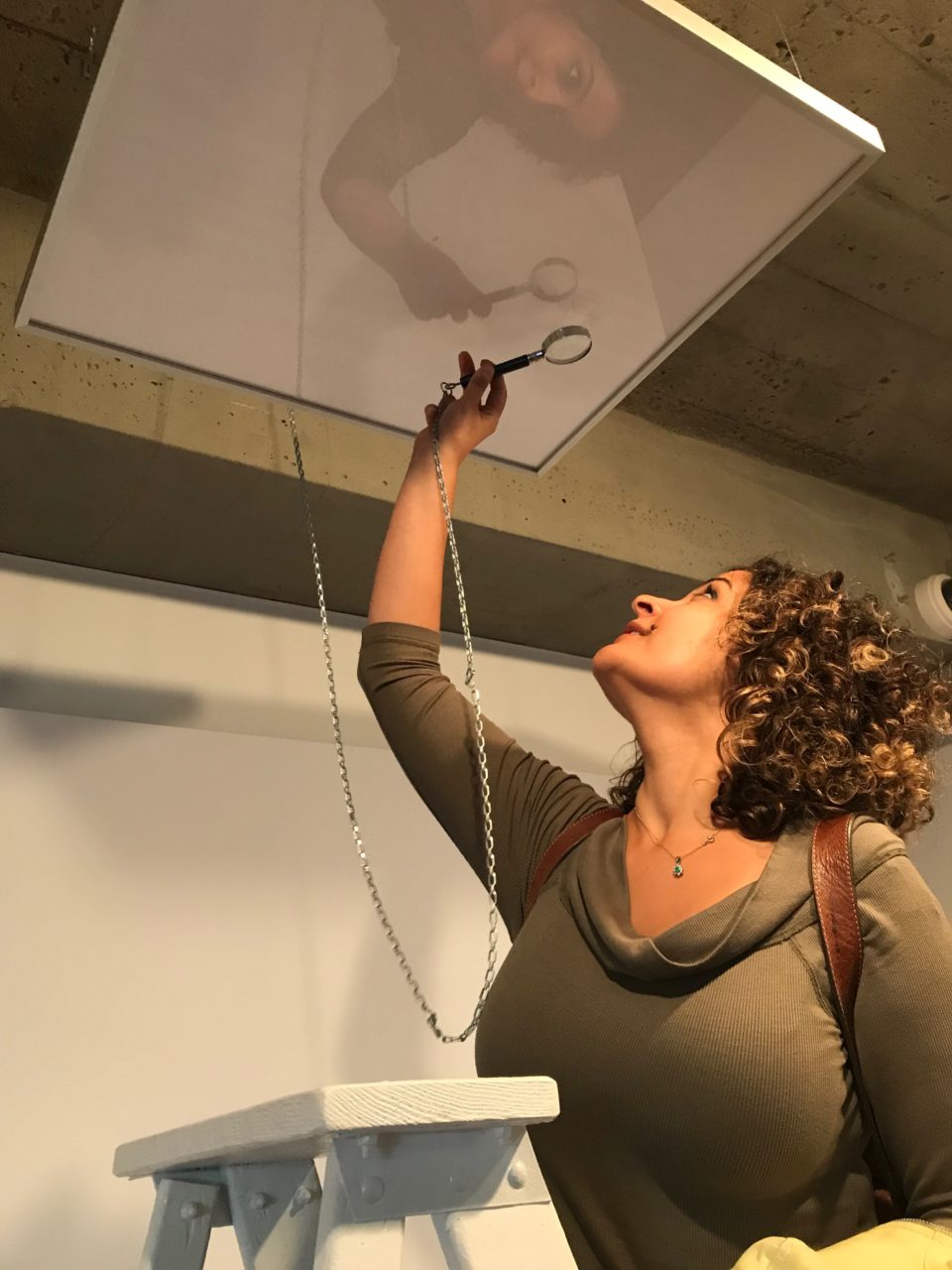

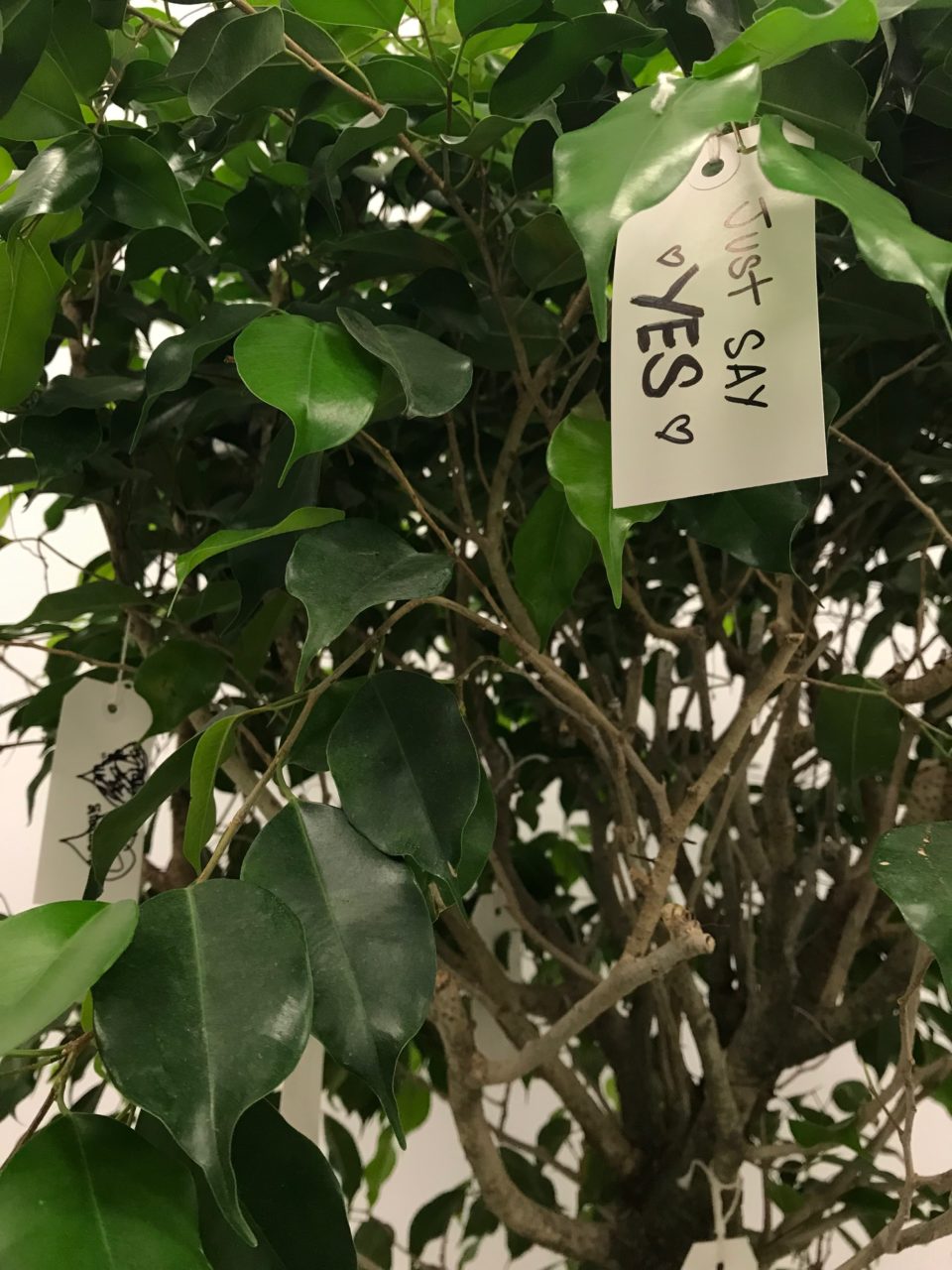

Many works whose staging includes a material element offer a degree of latitude for the gallery to tinker with. What this means, in effect, is that many instruction works have meta-instructions that Ono gives to galleries, and which they are granted freedom in imagining, interpreting, and implementing, just as the visitor faces choices for enacting instructions on a personal scale. Famously, John Lennon’s first encounter with Yoko Ono and her art was in viewing Ceiling Painting (also known as Yes Painting) at the Indica Gallery in London, in 1966. As he tells it, an awkward ascent up a rickety ladder and the manoeuvring of a necessary “spyglass” were rewarded when he contorted his long limbs to make out a small print “YES” on the ceiling. Gone were the low expectations that came with his perception of avant-garde art as loaded with negativity—dissipated in an affirmative rush after a precarious climb. At the very same show, because John had celebrity access an hour before the opening, the interactive Painting to Hammer a Nail (1966/2019) was still pristine. Upon meeting Ono, he immediately negotiated to use a pretend hammer and a pretend nail to hammer into the canvas—responding without hesitation to the cornerstone of imagination in her approach. Thus began his work and life partnership with the artist, inspired by a gratifying message of optimism, and the playful interactions that followed.

In the contemporary, corporatized climate of safety and liability concerns, the narrative drama and climax of Yes Painting are somewhat muted. Recent stagings use a stable stepladder. This is the route the PHI Foundation chose, aligning with the gallery’s mission to maximize public accessibility to art, including the terms of physical access. It is a more conceptual staging, to be sure. For many, neither the magnifying glass nor climb are necessary in order to read the word on the ceiling. But, as Ono herself has explained, the artistry of an instruction lies in the idea that the artist provides. This is evident in instructions to stare at the sun until it becomes square, or to cough for a year, or, in Fly Piece (1964), to “take flight”—put more prosaically, to jump off a ladder. As she told BBC Radio in 1968, “What I’m trying to do is make something happen by throwing a pebble into the water and creating ripples . . . I do not want to control the ripples.” To imagine is enough; even if you can’t physically do it, Ono tells us, if you “construct an idea in your head,” you have engaged. If this version of Yes Painting is eminently possible to perform, rather than as impossible as some other instructions seem, still the same principle holds: it is the concept, and the personal experience of the piece that matter.

Is there a canonical staging of a Yoko Ono work like Yes Painting, or does this notion fly in the face of the very idea of Growing Freedom? Is the idea of passing any sort of “Ono test” even relevant, when she seems to want to offer an infinity of prospects for all? If there is a staging that doesn’t pass muster, surely it must be the dispiriting iteration of Yes Painting at MoMA Oxford in 1998, which placed a “Please do not climb the ladder” placard adjacent. More than just lost drama, the expansive, hippie sense of possibility is cancelled out by an institutional injunction. The sign’s effect on the visitor experience is something to reflect on in the context of Ono’s central themes of peace and freedom.

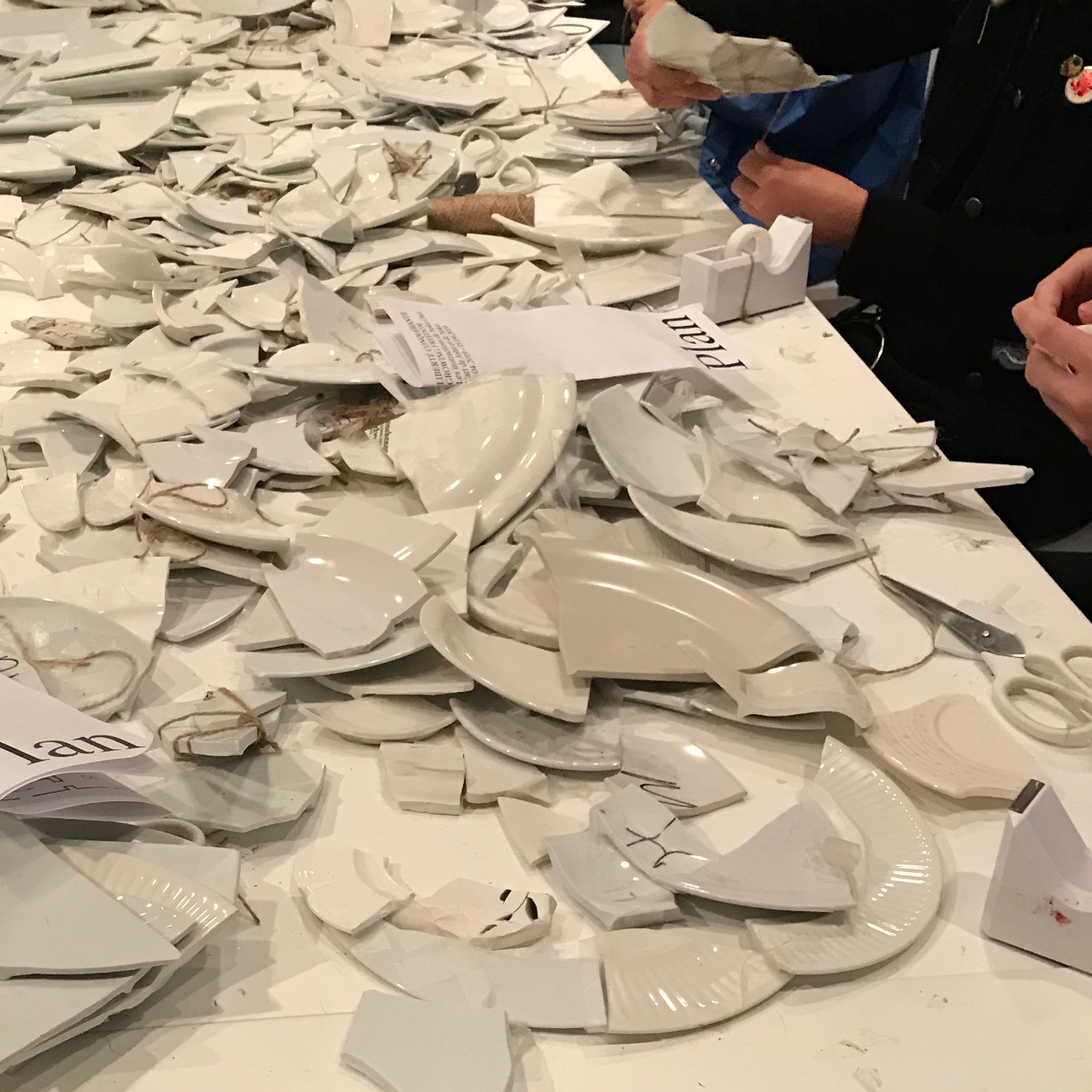

Mend Piece (1966/2019) is another oft-staged Yoko Ono instruction work. At the PHI Foundation, it was housed on the second floor of the exhibition: a set of eight chairs around a long table with piles of broken dishes on it, with the instruction to “Join fragments of ceramic pottery together, using the provided twine, tape, and glue, to transform broken fragments into objects.” Two Chelsea galleries showed Mend Piece concurrently in 2015, right after MoMA New York’s Yoko Ono solo show. The Chelsea exhibits were similar to each other, sharing the alternative instructions “Mend with wisdom mend with love. It will mend the earth at the same time.” They both featured a collaboration between Yoko Ono and coffee roaster Illy. Adjoining the gallery rooms were espresso bars serving customers in Illy brand cups, designed by Ono. The set was for sale, priced at $250, and sold exclusively at the MoMA gift shop before being launched online by Illy online months later. Kintsugi-inspired gold repair lines adorn the collection, marking the repair of catastrophic world and personal events, from Hiroshima, to the My Lai massacre in Vietnam, to John Lennon’s shooting.

Ostensibly, the coffee bars in the galleries were designed to keep people comfortable, in order to stay a while and create. At best this was a hospitable touch, but nevertheless a jarring commercial presence, which, like the museum directive at MoMA Oxford years before, formed a stark juxtaposition with the idealistic hippie throughline of Ono’s work. Any gesture in staging, even one that rubs the wrong way, can engender valuable reflection on what it means to be free. The multiple iterations of Yes Painting, Mend Piece, and Helmets, with their conspicuous layers of intervention, bring up pressing questions about the relationship of institutional authority and capitalist, corporate, and carceral structures to liberty. (In the follow-up exhibition to the Yoko Ono show, on view from November 8, 2019 to March 15, 2020, the PHI Foundation dives headlong with Phil Collins’s work into themes of liberty and carcerality, and the relationship of freedom to music.) The latitude—the freedom—Ono gives to the gallery opens up possibilities she cannot foresee, which one can’t help but think might be exactly what she wants. Otherwise, her collaborators aren’t using their imagination.

Two companion pieces to this article examine further collaborations with Yoko Ono at the PHI Foundation between April and September 2019. Changing the course of Water Event: from environmental racism to survival on the planet looks at how twelve Canadian, Quebecois, and Indigenous visual artists negotiated a half-century-old invitation from Yoko Ono. On Reclaiming Women’s Bodies, Voices, and Lives reviews a Montreal musical artist’s reinterpreted live performance of the 1960s Ono/Lennon anthem, “Give Peace A Chance.”

About the Author

Shirin Radjavi is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University. She studies the art and anthropology of the Iranian online fashion imaginary, with its references to transnational pop culture and centuries of Iranian political and material history. Her work documents how people constitute their past, present, and future at the intersection of global capitalism and local community practices. She also collaborates with Iranian filmmakers on English translations of their works. Recently, she has been listening to a lot of Motown.

Suggested Reading

Full-colour hardcover editions of the catalogues Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971 and Yes: Yoko Ono were available for perusal in the Traces module, a cosy armchair reading pod on the subterranean level of 451 Saint-Jean. The PHI Foundation’s catalogue of the show, entitled Yoko Ono: LIBERTÉ CONQUÉRANTE/GROWING FREEDOM, is available for purchase at gallery reception, among other books.

Biesenbach, Klaus, and Christophe Cherix, eds. 2015. Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971. (Catalogue). New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

Chung, Youjin. 2011. “Yoko Ono’s ‘Cut Piece’ as a Participation Work.” International Journal of the Arts in Society 5, no. 5 (April): 303–313.

Concannon, Kevin. 2008. “Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece: From Text to Performance and Back Again.” PAJ: A Journal of Performance & Art 30, no. 90 (September): 81–93.

Dimitrakaki, Angela. 1998. “Yoko Ono: Have You Seen the Horizon Lately?”. Third Text (42): 99–104.

Goodman, Amy. 2007. "Exclusive: Yoko Ono on the New Imagine Peace Tower in Iceland, Art & Politics, the Peace Movement, Government Surveillance and the Murder of John Lennon.” Democracy Now!, October 16, 2007. Retrieved August 14, 2019. https://www.democracynow.org/2007/10/16/exclusive_yoko_ono_on_the_new.

Lennon, John, and Yoko Ono. 2018. Imagine John Yoko. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Logie, John. 2017. “Remix: Here, There, and Everywhere (or the Three Faces of Yoko Ono, ‘Remix Artist’).” Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric 7, no. 2/3 (April): 116–129.

Rothfuss, Joan, and Midori Yoshimoto. “Early Objects: Works.” In Yes: Yoko Ono, edited by Alexandra Munroe and Jon Hendricks. New York: Japan Society and Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Meier, Allison. 2015. “Yoko Ono Asks Gallery Visitors to Repair the Impossibly Broken”. Hyperallergic, December 14, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2019. https://hyperallergic.com/261540/yoko-ono-asks-gallery-visitors-to-repair-the- impossibly-broken/.

Munroe, Alexandra. 2000. “Spirit of YES: The Art and Life of Yoko Ono.” In Yes Yoko Ono, edited by Alexandra Munroe and Jon Hendricks. New York: Japan Society and Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Papazian, Ellen. 2009. “20 Ways of Looking at an Art-World Icon.” Bitch Magazine (45), November 17, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2019. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/oh-yoko.

Sayle, Murray. 2000. "The Importance of Yoko Ono." Occasional Paper No. 18, Japan Policy Research Institute, November 2000. Archived December 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 14, 2019. http://www.jpri.org/publications/occasionalpapers/op18.html.

Photos: Shirin Radjavi (detail photos), Richard-Max Tremblay (installation views and cover photo)